For some reason I seem to be on a "literary" kick with my non-screenplay writing. Today's story is not a funny, upbeat tale but neither is it a creepy, disturbing bit of horror or one of my pitiful attempts to write action.

I started it last night on the train and finished up this draft on the way in today. Please let me know what you think, good and bad. Where there should be more, or less. If I should spend time forming it or let it alone and move on. That sort of thing.

On the Rails

By Jon Stark

May, 2014; about 2800 words

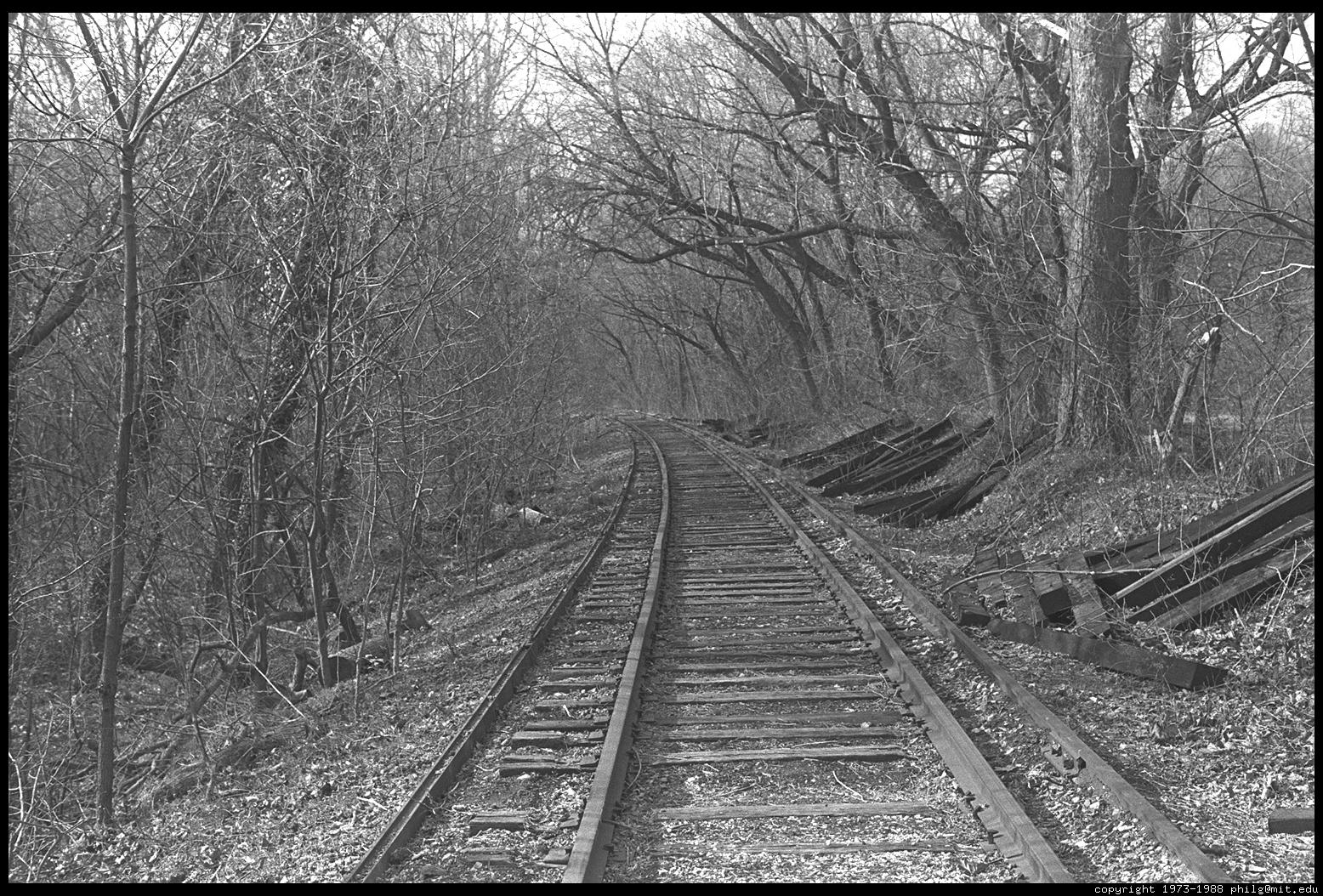

I’ve always liked trains. They have an order about them that reminds me of libraries and accountants. A timeliness and surety trenched in strong tradition, the hulking iron snaking through woods and swamp on a path that has always been there. I’ve seen crews repairing the roadbed and I’ve walked miles along deserted ballast, but I’ve never seen a new line going in.

I am clinging to that order. Everything else is upside down and sideways. Maybe not for you. But you aren’t the one who found him.

#

I suppose if I was a spy then I would always expect the unexpected and nothing would ever surprise me. James Bond always knew what to do when an assassin jumped out of his foldup bed on the train. I am not James Bond. Martinis make me sick – no matter how many times you shake them.

When I walked into my house I was not expecting anything other than my kid brother Tim – he was Timmy until he moved in with me – to be sprawled out on the floor playing video games or texting his girlfriend-of-the-week. I wasn’t surprised that he wasn’t there. He goes out a lot. Went out a lot.

When I got a glass of water from the kitchen I didn’t know it was the last time that particular glass would hold anything. No sense of its destiny, that it too would shatter against my bathroom tile. My dishes aren’t like the train. They don’t have that immutable characteristic of… there.

Art told me I should be glad that he was in the bathroom. “Lots of tile in there.” said Art. “And drywall. Not like a rug.” No. Nothing like a rug. Kind hearted souls have made that point several times since Art first shared that bit of wisdom.

In elementary school my best friend’s friend’s father skipped the tile too. He sat down at the picnic table in the backyard about two hours before his wife was due home from work -- fifteen minutes before the bus was due – and made sure there wouldn’t be a mess on the rug. Or tile.

#

When you get on the commuter train there’s a sort of dance that everyone does. They don’t have corrals like Disney World, just a long platform where you can gather wherever – like a field – and so we gather in groups – like sheep – waiting for the train. The smart sheep know where the doors will be when the train stops so we stand with them. They know from years of experience and watching others, now long passed on, who knew, because that’s the place on the platform where the doors open. This is a train and it is eternal, unchanging and always there.

The same people stand in the same flocks, the readers and chatters and the impatient ones who somehow think that by weaseling to the front they’ll get home sooner. It’s a train. You can’t change anything about it. Time is set by the train.

The dance is comforting, a constant milling about like emperor penguins on the ice making sure they don’t freeze to death. I feel frozen. There’s the man with the stomach problem that always tries to cut. I don’t even try to stop him. Someone else will. And when the train comes we’ll all either have seats or we won’t. And it won’t matter about the man and the smell of his lunch because he didn’t find Tim.

#

I called Art first not because he is my best friend but because he knows about this sort of thing. He grew up in the funeral business. “Lots of money if you’re sharp, but the clients always try to stiff you.” I didn’t think it was funny the first time. It’s all I could think of when he came to the door.

The third time I heard him make the joke we were at Woody’s Creekside and he was trying to make one of the college girls laugh. She didn’t laugh but they left together so I was sentenced to hearing it hundreds of times more. It isn’t that Art is a jerk, exactly, he just sort of got detached about death growing up with a basement full of corpses.

“I’m really sorry.” he told me. “Where is he?” I took him upstairs. Showed him the bathroom door. Closed. As if quantum theory was real and as long as the door was shut and we didn’t look, it would still be okay.

But I already knew. I had looked. It was real. And I couldn’t go back in. Tim didn’t care. He was long gone. Art only needed a minute. “At least he did it in the bathroom.”

The police came. All of them, I think. They said they were sorry, said I wasn’t in any trouble. “No foul play.” assured the woman in charge. “You’re clear.” Easy for her to say. I wanted to scream at her, to ask her how it was possibly not my fault he was – like that now.

I mean, think about it. If it had been drugs you could blame the dealer. For cancer you could blame anyone from the power company to the foster mother who never gave us vegetables. If he’d been the passenger in a car of a drunk teenager you could blame Scott. But this was different. This was a big fat finger pointing straight at me saying, “You let me down. You failed.”

#

There was a stranger on the platform this afternoon. He was a late comer, showed up as the train pulled in. Went around the flock, tried to slip in front of me. I dug in my heels. Not this time. I let the lady who works upstairs go because she was a lady and I sort of knew her and she works in the CEOs office and I always let her go and she doesn’t know me from anybody but if I didn’t let her then she would find out about me and I’d probably get fired. But I didn’t let the stranger go. He got into my space and usually I would have caved but I’d already quit on the fat man and Tim had quit and I wasn’t going to quit again. Ever.

Not that that train cared. The train didn’t know about Tim. It didn’t know about my bathroom and the tile. It just was. And the doors closed us in like they always have.

#

Art took care of the paperwork for me. He knew all about it. Called his father about the initial arrangements. “I know you aren’t thinking about this right now, but you don’t have to worry about it. Dad’s going to take care of everything for you. No charge. He’s really sorry, wanted me to tell you.” I wasn’t sure why Art’s dad didn’t tell me himself so I asked him later, when everyone else was gone and we were on my porch drinking the last of the Milwaukee’s Best he’d brought over.

“Dad doesn’t really do grief. He’s a professional ‘I’m so sorry’ sayer so when it’s personal he doesn’t know what to say.” That seemed really strange. “He’s afraid it comes out all businesslike instead of from the heart.” Art crushed his can. “I think he’s pushed it all so far away he doesn’t want to risk bringing it back. Bad for business when you fall apart in front of your clients.” I waited for the joke but he was silent.

“I really am sorry. This sucks.” said Art. “This really sucks.” It was weird for me to watch my best friend fall apart on my porch at two in the morning, an army of empty cans at our feet, bawling his eyes out over my brother. It should have been me. Not on the tile, but falling apart.

But then again, Art wasn’t the one who found him.

#

People do all sorts of things on the train. Sleep. Read. Play Bejeweled. Somebody always shares their personal life in a one-way, high volume phone conversation. I used to be one of those people, wasting minutes on stuff. Now I sit in the zone of isolation that the etiquette demands and stare. Not out the window. That’s always the same, always has been. I stare at the banality of everything. The cup holder. The sign for the next stop. I stare at the lady with wispy orange hair. These people know nothing about me.

I know nothing about them. How many of them have a ruined bathroom? How many of them will ruin their bathrooms? Or picnic tables?

A thousand yards ahead of me the engine’s whistle blows – a warning? a greeting? Where are we going?

#

Art was true to his word and the arrangements were taken care of. He also called Sue that first night. “Did you call Sue?” he asked me before we started drinking. I hadn’t. Hadn’t thought about Sue. She’s our sister and I was quite sure that she hadn’t thought about me or Tim in days. Maybe months. Maybe since I sent her the Christmas card last January.

“I’ll call her.” he told me. Whatever. I didn’t know what to say. Sue made my life very hard growing up. The only thing worse than being unpopular is being the unpopular brother of the most popular girl in school. Do you have any idea how awkward it is to be in the locker room and listen to other guys talk about your sister? Describe what they’d do? Prognosticate about what she looks like naked? The first time one of them shut down the conversation by saying he knew exactly what that was like, I got a two week suspension for fighting (and a broken nose) and got home to find out that it was true.

“Go ahead.” I told him. “Call her.” The only thing worse than the locker room was having a friend crush on your sister. He was gone for two and a half beers. “That was a long time.”

“Was it?” If I had been a bit more with it, not in the pre-depression glaze of denial, I might have noticed his mood change.

“She’s coming out tomorrow. Don’t worry about it. I’ll pick her up at the airport.” He sat back in the rocker, sighed like he’d just finished a good meal. “She was wondering about a hotel but I told her she could stay here.” He looked over at me. “You don’t mind, do you?”

“There’s only the one bathroom now.” And there it was. I was officially a jerkwad of a brother.

Art brushed it off. “I’ll take care of that in the morning.”

I was surprised to find out that Randy didn’t come out with her. I knew things weren’t great between them, but I didn’t know they were that bad. I told her she could stay with me as long as she wanted. My house was her house. All the usual. She said thank you and I expect her to be there when I get home tonight but she won’t stay much longer. She doesn’t like it here either.

#

I had a lot of toy trains when I was growing up. I would spend hours laying down track and pushing them along. Then just watching as I grew older and the trains could move on their own. They went where they were supposed to. Nothing unplanned. Nothing unexpected. So different from the system that moved us from home to home.

I only had so much track and would often set up the same layout over and over. It was like the train had always been there, always the same. It was only gone because I had turned my back. It didn’t matter that the houses were different.

I keep thinking that Tim is only gone because I turned my back. That at any moment he will jump up from the couch and ask me to take him to the Jade Dragon for General Tso’s. All we had to do was walk in. They knew us there. They pointed us to our table and brought the waters and hot tea and crispy noodles. The only question was whether or not we wanted fried wontons. The old man, the father I think, always sat at the cash register behind the bar. Always the same greeting, always the same clothes.

If it had been politically correct I’d have thought he was descended from the railroad. He has that same timeless quality. For a moment I consider going there. Maybe Tim is waiting for me. But I know better. And I know that that old man will still be sitting on his stool because he doesn’t know how the world has changed.

He isn’t the one who found Tim.

#

Art doesn’t work for his father. “After Scott’s accident I knew I couldn’t do it.” he told me in confidence one night at Woody’s. “Man, that was awful. You know they found his sneaker with the foot still in it?”

“Right or left?” I asked. I still don’t know why that was important.

“You are sick, you know that?” he said. I didn’t bother pointing out the irony. “It was his left.” He started drinking a shot of Jack with each beer after that. “I just couldn’t do it if it was going to be someone I knew. Someone young, you know?”

I did know. I couldn’t have done it for someone old either, but he grew up with it, like I said. The thing about Scott’s accident though, that sort of tore our whole school up. He was a senior and he wasn’t the only one who died that night. He was just the one everyone blamed and, since he was driving, it was his accident.

We talked about Scott the second night after my bathroom was ruined. The night my sister came into town and moved into the guest room and hugged me, holding on so tight I thought I might still have purpose.

But about Scott. Cops found him and the girls. Not his older brother. I’m sure it was hard for them, but it’s their job. My job is to push paper. I’m not trained for finding the parts of people that get separated during ‘MVAs’ – I don’t have jargon like ‘MVA’ to protect me from the harsh reality of a motor vehicle accident, the carnage and tragedy. I wasn’t trained for finding the parts of me that were separated during that accident.

“Thing is,” Art was saying, “I’m not sure I can keep going now.” Art had his own company, “The Morning After,” which was a service that specialized in cleaning up after someone died – houses were about a third of his business. The bread and butter though was hotels. “You have no idea how many people make a mess of their hotel rooms.” He was right. I didn’t.

Art had brought a 24 pack this time since there were three of us. I don’t like Milwaukee’s Best enough for that so I’d grabbed my bottle of gin. We’d made pretty good progress as a team. “When it’s a stranger, it’s just a mess. But when it’s somebody you know, that’s just different.” He waved his hands around.

“How so?” I really wanted to know.

“Take the brain. It’s a nasty mess to clean up and usually full of bone fragments and stuff. Usually you just wear gloves and scrape away but when it’s somebody you know?” He paused long enough I thought he’d passed out. He hadn’t. He was breaking down. “Those bits of brain are where the jokes were that made you laugh. The memories of doing stuff with you. The secrets that you shared.”

That explained why my bathroom was still off limits. Why this one thing that he’d said would be taken care of hadn’t been yet. “Do you want me to hire someone else?”

“What kind of a friend would that make me?” I wasn’t sure, punch drunk from the death of my brother, gin drunk on my front porch, watching my sister lean against him instead of Randy.

#

When you look down a railbed you see two lines that run together into infinity. If you look the other way you see the same thing. But when you ride the train you can’t see in front of you or behind you. You just sit there, rocking back and forth, borne along by faith, waiting to see where you are when the doors open.

No comments:

Post a Comment